Unusual vagrants made the first half of November, 2012 extraordinary for mega-rarity bird sightings in southern California. From the 4th-7th of November, an Ivory Gull visited Pismo Beach. Then on the 8th, a Black-tailed Gull appeared in Long Beach. On the 9th, someone found a Taiga Bean Goose at the south end of the Salton Sea. The Ivory Gull was only the second one seen in California. The Black-tailed Gull was a third state record and the Bean Goose is a first. Of these unusual vagrants, the latter two are normally found in east Asia. Are these just random occurrences or are they part of a larger pattern, perhaps resulting from climate change?

Ivory Gull

Ivory Gulls are native to the far arctic where they live on pack ice and feed mostly on the carcasses of dead mammals such as seals. As the name implies, the adults are almost pure white. The only coloration is their black legs, feet and eyes, and their bill, which is greenish with a bright yellow tip.

In the 20th Century, Ivory Gulls reached the US in the Lower 48 and southern Canada in only 20 of 100 years. Few of these years had more than one bird, and most were first winter birds. Since then, Ivory Gulls have “vagrated” to the Lower 48 and southern Canada in 8 consecutive winters, and most were adults. In fact, the Pismo Beach bird was the 8th for 2010 alone, and ALL of them were adults. The vast majority of North American records are from the northeast, but recent records from Tennessee (1997), the Alabama/Georgia border (2009) and Pismo Beach are unusually far south. The Pismo Beach record is the earliest fall/winter sighting ever – typically, sightings occur between December and March with the bulk of those in January and February. See “Patterns from E-Bird” at eBird.org for more complete sighting details.

Ivory Gull

Ivory Gulls normally stay close to the Arctic Circle and are quite comfortable in that harsh environment. They have long claws, adapted for traction on the ice, but the claws are of little use on a beach where people wade barefoot in the ocean. The availability of multiple seal carcasses along the beach certainly helped keep this Ivory Gull fed. While we were there, it spent most of its time feeding.

Vagrancy among juveniles can be attributed to a successful breeding season, but among adults, it is more difficult to explain. Perhaps because Ivory Gulls rarely see humans, they are often relatively tame. At Pismo Beach, birders frequently surrounded the gull. Joggers and dog walkers passed by, but the gull seldom flew in response to close approach. The dramatic changes in vagrancy patterns may be cause for concern about this already endangered population of Ivory Gull. Seeing one this far from the pack ice was incongruous, but delightful.

Black-tailed Gull

Black-tailed Gulls are native to eastern Asia but are casual visitors to coastal Alaska and northeastern North America. They are accidental in California. Neither of the two previous records were chase-able. The first bird visited San Diego Bay in 1954. It was collected. A visiting birder photographed the second one at a public beach in Half Moon Bay (12/29/2008). Many birders searched, but never refound the gull.

Black-tailed Gulls are native to eastern Asia but are casual visitors to coastal Alaska and northeastern North America. They are accidental in California. Neither of the two previous records were chase-able. The first bird visited San Diego Bay in 1954. It was collected. A visiting birder photographed the second one at a public beach in Half Moon Bay (12/29/2008). Many birders searched, but never refound the gull.

Black-tailed Gulls are larger than Ring-billed Gulls and smaller than California Gulls. Adults have a bright yellow bill with a red spot followed by an uneven black ring and a bright red tip. The face shows bright white eye crescents above and below the yellow eyes with their red orbital ring. They also have yellow legs and feet. Despite the name, the tail is not completely black, featuring a broad black sub-terminal band between a white rump and narrow white terminal band. The mantle is slate gray, and their wing tips have much smaller white mirrors than other medium to large white-headed gulls.

The Long Beach Black-tailed Gull remained through at least the afternoon of the 10th. It stayed in its general location all day, moving only between the beach, the water, and some buoys. The bird was absent when we arrived pre-dawn on the 9th and only a few gulls were on the beach, but it flew in at 6:15 AM to the delight of about 30 birders, some of whom came from as far away as the Sacramento area. While on the beach, the it spent much of its time preening in the midst of a flock of Ring-billed, California and a few Western Gulls.

Taiga Bean Goose

In 2007, the AOU split Bean Goose into Taiga Bean Goose and Tundra Bean Goose, based on breeding habitat: forest bogs in the subarctic taiga or on the arctic tundra. The Taiga Bean Goose has a black bill with a yellow-orange tip. It lacks the white at the base of the bill of the Greater White-fronted Goose (which has an orange bill). A longer bill, and narrower at the base, distinguishes it from Tundra Bean Goose. Bean Geese have a habit of grazing in winter bean field stubble, hence the name. Bean Geese are native to Eurasia, and the Taiga is the largest species.

In 2007, the AOU split Bean Goose into Taiga Bean Goose and Tundra Bean Goose, based on breeding habitat: forest bogs in the subarctic taiga or on the arctic tundra. The Taiga Bean Goose has a black bill with a yellow-orange tip. It lacks the white at the base of the bill of the Greater White-fronted Goose (which has an orange bill). A longer bill, and narrower at the base, distinguishes it from Tundra Bean Goose. Bean Geese have a habit of grazing in winter bean field stubble, hence the name. Bean Geese are native to Eurasia, and the Taiga is the largest species.

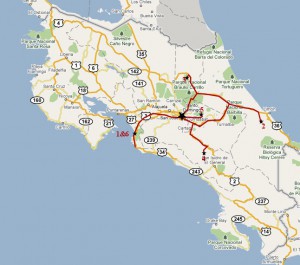

This individual showed up at the south end of the Salton Sea at Unit 1 of the Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge on Vendel Rd. This Taiga Bean Goose is of the Middendorf race from eastern Siberia, which may merit separate species status itself. There are only about 5000 Middendorf’s Taiga Bean Geese. This goose associates with a huge flock of mostly Snow and Ross’s Geese that also includes three Greater White-fronted Geese. Other North American Bean Goose records were mostly from coastal Alaska, along the Aleutians or in the northeast (US and southeast Canada). There are also two 2003 records from the state of Washington.

Why the Vagrancy?

The question many California birders ask is: why are we seeing these mega-rarities all in southern California in early November? Could these occurrences be due to climate change? Some evidence may support that conclusion in the case of the Ivory Gull. However, there is as yet no causal connection between climate change and the vagrancy of the other two birds. Regardless of the reasons, it sure is an exciting time to be birding in southern California!